WHY YOUR IRA MAY NOT BE THE GREAT INHERITANCE YOU THINK IT IS

When it comes to protecting your wealth against taxes, lots of advisors warn against estate taxes. But for the average American—those who fall under the $13.99 million ($15 million for 2026) estate tax exemption—the more relevant concern is income tax.

If you plan to gift any of your wealth to future generations, it’s important to understand how taxes could impact your giving strategies—particularly those related to inherited IRAs.

Tax implications of inherited IRAs

Many of my clients allocate a significant portion of their savings to pre-tax accounts like 401(k)s. This can be a great way to grow money tax-deferred for retirement, but it’s important to remember that when you distribute the money, it becomes taxable income.

Because of this, pre-tax IRAs aren’t usually retirees’ first choice to draw from in retirement (because who wants to pay taxes, ever, right?), but I encourage my clients to spend these accounts earlier as appropriate for their goals. Here’s why:

Many of those same clients also assume their IRAs will be a valuable asset to pass on to their children—but they neglect to consider the negative impact this type of gift could have on their children or grandchildren’s tax basis. Because when anyone other than a spouse inherits an IRA, it becomes taxable income—which, depending on your beneficiary’s stage of life, could inadvertently push them into a higher tax bracket and leave them with a significant tax bill.

This only recently became a problem, though.

How the Secure 2.0 Act affects Inherited IRAs

Several years ago, beneficiaries could take a “life expectancy distribution” from an inherited IRA, which allowed them to withdraw a certain amount of money from the account every year while the funds continued to grow. This meant if the account was managed well, it could continue growing and even pass on to another generation, without anyone receiving the burden of a lump-sum distribution and its subsequent tax liability.

But when the Secure 2.0 Act passed at the end of 2022, it changed the distribution requirements for inherited IRAs. Under the new law, beneficiaries must distribute all the funds from an inherited IRA within 10 years.

This is a problem for a few reasons:

Many people receive inherited IRAs in their highest earning years. It’s the nature of life—most people are at the peak of their careers in their 50s or 60s, which is also when many people lose their parents. And because inherited IRAs are taxed at the beneficiary’s income level, this could mean paying more taxes on the distributions than if the original account owner had distributed the funds themselves. After all, most retirees are in a lower tax bracket than their income-earning children.

Plus, the distribution amount added to a beneficiary’s current income could place them in an even higher tax bracket. For example:

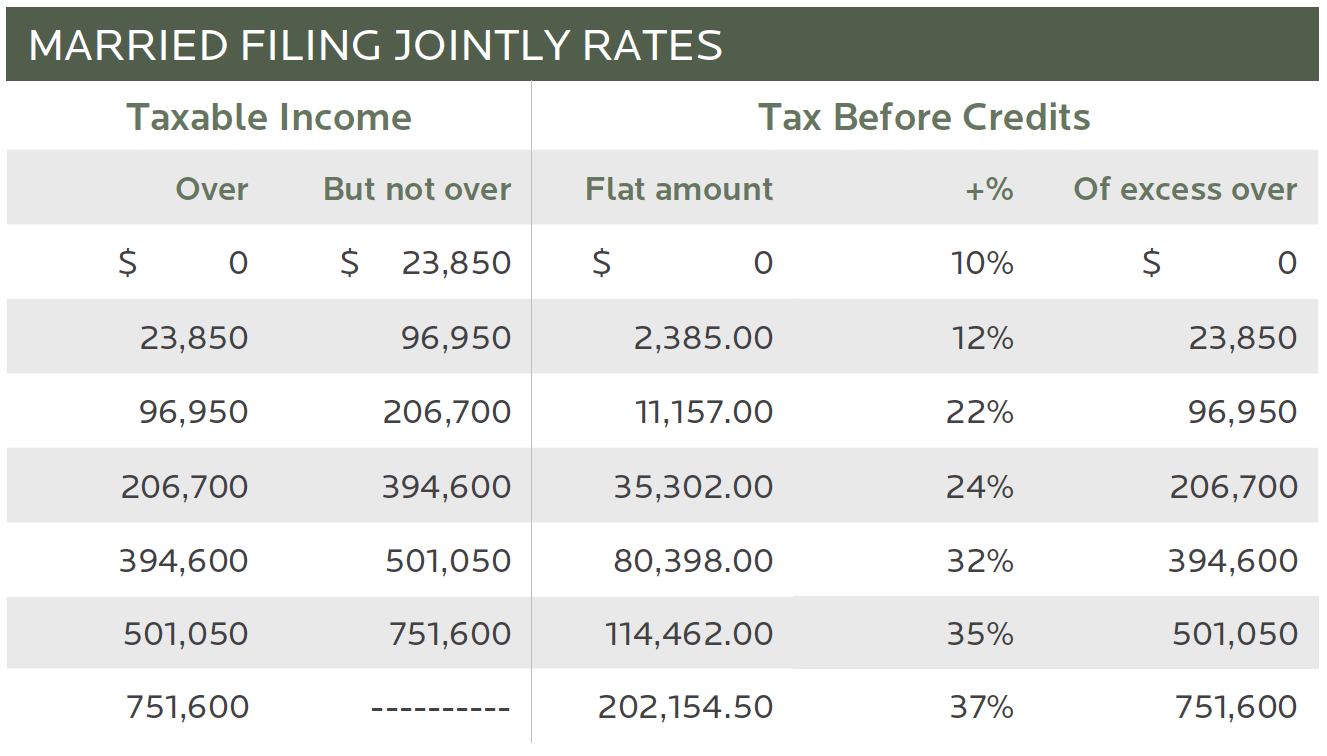

Let’s say you’re married and filing jointly, and you and your spouse make $200,000 annually. This puts you in the 22% tax bracket. If you inherit an IRA worth $500,000, you could be adding $50,000 to your income each year for 10 years—putting you in the 24% tax bracket for those years1.

1 Quick View Tax Guide, 2024 and 2025, page 3, New York Life

That’s not to mention what you would pay if you decided to let the account grow over the 10 years before distributing it all at once. At that point, the account could be worth $1 million, and you’d be responsible for the taxes on that income.

(I think it’s safe to say the IRS was thinking about our multi-trillion-dollar debt problem when they made these changes to the tax code.)

So while many retirees imagine a nice 50/50 split of their assets to their two kids, it often ends up being a 30/30/40 split—with the IRS being the biggest beneficiary.

Minimizing the tax burden on inherited IRAs

The reality is, nobody wants to pay taxes. So most retirees avoid spending their pre-tax accounts as long as possible—but I recommend the opposite.

If your goal is to gift your remaining assets to your children or grandchildren, it makes more sense to live on these pre-tax accounts as much as possible during your lifetime—rather than pass the tax burden on to your higher-income-earning children.

Another strategy is to take larger distributions from your IRA and put the money in a taxable brokerage account—this way, your beneficiaries receive a step-up in basis when they inherit the funds.

Something else to consider is a Roth conversion, where you convert your pre-tax account to a Roth IRA and pay taxes on the conversion. Then when your beneficiaries inherit the Roth, they don’t have to pay taxes on the distributions. (They will have to distribute everything within 10 years—the IRS doesn’t want that money growing tax-free forever, after all—but this is favorable to them paying income taxes on those distributions.)

Doing What’s Best For You

Of course, you have to weigh the pros and cons of each option as it relates to your situation. Not every beneficiary will be in a higher tax bracket than their benefactors, and changing your taxable income in retirement can affect how much of your Social Security benefits are taxable.

There are a lot of factors to consider, which is why it’s wise to work with an advisor who understands your situation—whether you’re planning for retirement and considering your gifting options, or you just received an inheritance and want to minimize your tax burden.

I’ve helped clients in both scenarios, and we can work together to determine the strategy that’s best for your current needs as well as your long-term goals.

If you’d like to discuss your situation, or you have questions about inherited IRAs, I’d be happy to meet with you.

1 Quick View Tax Guide, 2024 and 2025, page 3, New York Life